“Inviting our thoughts and feelings into awareness allows us to learn from them rather than be driven by them.” ~ Daniel Siegel

In part one we looked at a foundational aspect of communication – embodied listening.

In part two we explored how vital clarity is to keeping yourself and your conversations on track.

In part three we will be diving into some physiological reasons why staying present and why the ability to express oneself can be a challenge when stress levels increase.

The Brain

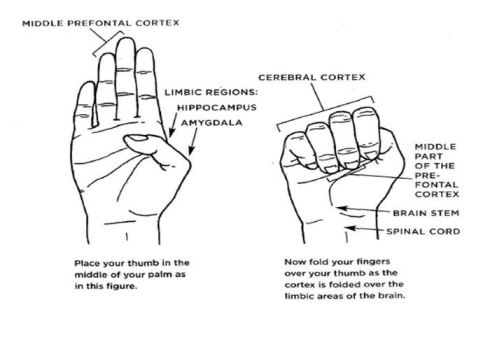

An effective and simplistic way to understand the brain is Daniel Siegel’s widely known hand model of the brain.

- The reptilian brain – The wrist (spinal cord) and palm (brain stem) regulate basic bodily functions such as breathing, heart rate, and survival instinct. This survival instinct is responsible for the fight-flight-freeze response.

- The mammalian brain – The thumb (limbic area) together with the wrist and palm process emotion, sensation, motivation, memory encoding, and attachment in relationships.

- The cerebral cortex – The fingers (cerebral cortex) are responsible for such things as consciousness and cognition. The ring and middle finger (medial pre-frontal cortex) aid us in awareness and attention. All together our fingers are responsible for executive functioning. As well, they help regulate our nervous system, calm fear, and attune to others through empathy and compassion.

Our brain on heightened emotion

Painful experiences, referring to the hand model, are stored in the thumb. These memories become generalized so that we are not required to repeat the same lessons over and over again; this a conditioned response based in survival and self-protection.

If something in our internal or external environment is suggestive of a painful memory the fingers go offline; this only takes a quarter of a second to occur. As Daniel Siegel says we “flip our lid”. This means our ability to attune to another person is diminished and reasoning is stalled. Adrenaline levels surge and the sympathetic nervous system amps up, creating a fight-flight-freeze state. If you recall some previous experiences I am sure you have some familiarity with this response; a sudden sense of overwhelm and the inability to stay focused on what your partner is saying.

“Our state of mind can turn even neutral comments into fighting words, distorting what we hear to fit what we fear.” ~ Daniel Siegel

Soothing

When in a state of sympathetic arousal, finding ways to soothe oneself is necessary before trying to continue a conversation. Soothing can begin by connecting with your partner(s), saying their name(s), or a gentle touch (if that feels right), followed by identifying the precise emotion/sensations that you are experiencing. When we identify emotion accurately, calming neurotransmitters (chemical messengers) are released in the brain.

Another way to do this is to name the impulse you are having. “I am aware that right now I want to run away from this conversation. I need some time to reconnect with myself before we continue.” Or “It is getting hard for me to focus, I am having trouble listening. I need (define an amount of time) to ground myself before we carry on.”

If you notice your partner having trouble focusing you can pause and check in with them; say their name and identify the physical response you are seeing. This is about stating what you are witnessing, not about how you are interpreting it. For example, “(Name), I am noticing that you are looking around the room a lot. Are you able to hear me right now?”

Fine tuning attunement

The priority for everyone in the conversation is to reduce pain and remain present. It is important to understand that there is a difference between how support, abandonment, and accountability show up in conversation. Support is the ability to witness your own distinct experience while remaining receptive to your partners unique experience. Abandonment is when you deny your own needs or sense of self to try and resolve the problem. It is normal for there to be discomfort when practicing new ways of communicating. Accountability is acknowledging when you have acted in an unwise manner that has contributed to your partners distress.

This is not about caretaking, blaming, or fixing the discomfort, rather it is an opportunity to bring the anxiety into light. Simply speaking about it can lessen the power it holds in that moment. Asking for what you need to keep the conversation moving forward will help you as a couple come closer together.

Tools for re-establishing sense of Self

I recommend that each person prepare a list of effective soothing practices that support self-regulation. This list might include such things as: breathing techniques, looking around the room at your favourite item and describing it, pressing into a wall, moving your body in a conscious and intentional manner.

I can’t stress enough the importance of finding functional and supportive ways to self-soothe. Developing this tool box will help you in many aspects of your life.

Being regulated allows us to continue conversations without confusing our past with our present. It takes practice to become aware of when we are disconnecting and becoming reactive. The practice is to reflect inward with compassion and be honest about what we are experiencing and what we require. We can also support our partners’ process by gently reflecting back to them what we are seeing.

Navigating this process together we develop the skills that help us trust ourselves and our partners with our pain. When it comes down to it, we all really want to know that our partners will be there for us, meaning that they will hear us, see us, and receive us as best as they can.